|

|

|

Page 5 |

Newsletter 114, Autumn 2016 © Hampshire Mills Group |

Cornwall Study Trip - Part 1

Sheila

Viner

Photos by Keith Andrews, Eleanor Yates, and the

author

|

|

Thursday 19 May saw an early morning start from

Hampshire for 11 HMG members as we set off for our

four day Cornwall Study Trip; Mick Edgeworth was to

have been ’twelfth man’ but, having sustained a back

injury, had to opt out. Several of us were picked

up from Eleanor Yates’s and Ruth Andrews’s houses in

Winchester where we were generously allowed to leave

our cars. Andy Fish once again was our driver and

he took us on an enjoyable route which followed the

coast road through Dorset, joining the A30 through

Devon.

We arrived at our first mill of the trip, in the

Tamar Valley on the National Trust estate of

Cotehele, just over the Devon border in Cornwall. A

pleasant, leg stretching walk from the car park

through woodland alongside the stream to the sturdy,

stone built Cotehele Mill gave us an energising bit

of exercise.

|

|

Inside we chatted with both John (in charge of the

weighing and bagging process) and Sally Newton who

became the miller in 2011; she had learned her

flour milling craft skills from Geoff Wallis at

Houghton Mill in Cambridgeshire. The previous

miller, Peter Langsford, was the last in his family

who had worked the mill for nearly a century,

retiring in the mid-1960s. In 2001 The National

Trust restored this mill to full working order

producing flour again.

|

|

|

|

We, having learned about Cotehele Mill’s history,

went and had a good look at the cast iron waterwheel

fed from a high, long, wooden launder; its 56

buckets each hold 9 gallons of water and, when

milling on their regular 2 days a week, normally

rotates at four revs per minute; at that speed it

can produce a maximum of 8.7hp/6.5kw as part of the

estate’s hydroelectric scheme. Originally the wheel

powered 2 sets of stones but only one set is used

now.

An amble further up the path led to the turbine hut

where there was a good, informative display and

sight of the plant, powered independently of the

mill from the Morden Stream, typically producing

3.7kw at 230 volts with a modest amount contributed

to the National Grid. On the path to the mill we

had passed through a cluster of stone buildings

which are now housing craftsmen producing pottery

and chairs formed from Cornish timber. It is also

possible to holiday there in self-contained mill

cottages.

|

|

|

Hidden in a deep valley just a few miles away at

Veryan, our next mill was built in the 16th century

of stone replacing earlier wood constructions. We

found a warm welcome of home-baked scones, clotted

cream, and pots of tea were waiting for us.

Although no longer working, the little Melinsey Mill

still has all its grain milling equipment and a 16ft

iron waterwheel, cast in a Truro foundry in 1882;

artefacts from other local trades such as sawyer

and blacksmith were stored and on show, whilst a

willow man and other willowcraft creatures, made by

the owner, awaited the more adventurous among us

along a winding path beside the small river.

|

|

Our visit here was a delightful interlude in an

enchanting place and we reluctantly left, but, we

were wearying and so sped on to our accommodation

for the next 3 nights at the Travelodge just outside

Bodmin. Once installed, we only had a matter of

yards to trek for our evening meal as a licensed

restaurant had been built right next door.

The Blue Hills Tin Streams was our first destination

of day two and our introduction into Cornwall’s

mining industry and what a superb visit this was –

excellent displays, detailed demonstrations and

explanations covering every aspect of winning pure

tin. Mark Wills learned the art of tin stream

mining from his father as the Wills family were

tinners for generations and owned this site.

Originally the tin streamers worked the alluvial

sands and gravel on the beaches and valley floor,

becoming miners later, tunnelling into the hillsides

and sinking shafts deep below. The Blue Hills Sett

became, in 1810, a co-operative of the many smaller

mines giving employment to 100 men and their

families until it closed in 1897.

|

|

|

|

|

We watched how the tin was ‘teased’ out of crushed

raw ore with Mark’s deft movements panning on a

Cornish shovel. We then went outside to see the

water-powered stamps crushing the blocks of ore.

The alternated, calibrated movements of rise and

fall of the stamps were mesmerising.

Next we heard about the sorting of ores, then

washing and jigging – where the shovel is now

replaced by a sloping, grooved flat bed with water

played onto it and a mechanism to jiggle the

assorted ores into various collecting tanks. Women

played an important part in this industry carrying

out many of the sorting and washing tasks by hand;

they were called bal maidens. Another craft Mark

Wills has developed is in making fine, pure tin

jewellery which can be purchased in their shop. I

bought a peace dove pendant to wear as a tribute to

the families who had endured such tough working

lives.

Andy Fish’s superb driving skills, already

demonstrated on the increasingly narrow, and

tortuously steep winding lanes to and from the Blue

Hills Tin Streams, steered our valiant minibus to a

superb lunch of a freshly baked, traditional Cornish

pasty at Philps family bakery in Hayle (see front

cover).

Thus fortified we headed for the ‘mine under the

sea’ which is in the St Just Mining District, now

forming part of the Cornwall and West Devon Mining

World Heritage Site. One of the most ancient hard

rock tin and copper mining areas in Cornwall it is

now owned by the National Trust. The Levant Mine

and Beam Engine originally opened as a copper and

tin mine but, tin proved the more abundant of the

two elements. Surprisingly arsenic was a lucrative

but deadly by-product of tin ore that was used all

over the world as an insecticide.

Levant Mine first appeared on a

map in 1748 but the Levant Mining Company was not

formed until 1820; the next 110 years saw a number

of highs and lows in their fortunes. Tragedy had

struck the mine in 1919 when 31 miners plunged to

their deaths as a connecting rod on the man engine

(which was to have taken them down to the working

levels) broke. |

|

|

|

The Levant whim engine is the only one of its kind

still working in situ: it is a beam engine, double

acting 24inch cylinder with a 4ft stroke, built by

Harveys of Hayle in 1840 and rebuilt by Hocking &

Loam in 1862 with a new cylinder and valve-gear

after an accident which caused the flywheel to be

thrown through the roof! This engine worked

continuously for 90 years at its task of raising ore

and only stopped when Levant was abandoned in 1930.

Levant Mine had subsea levels reaching out to

distances of up to 2 miles.

Whilst men endured highly dangerous and

uncomfortable work practices their womenfolk endured

backbreaking and arduous tasks in completing the

production of pure copper and tin. During the 19th

century women broke clods of ore, sorted and dressed

it during a long working day of 7am to 5pm

regardless of age, ranging from 9 to 90. The

majority of work was done in the open air and the

bal maidens were expected to work in almost all

weathers, only stopping if the water for dressing

the ore had frozen or had failed due to drought.

The coastline and geography combined with the

abandoned workings evoke feelings of raw beauty,

plus sadness and awe at the tenacity and endurance

of the Cornish in those times.

|

|

|

Lamorna was our last destination of the day and we

arrived to see the little Kemyel Mill tucked against

a steep hillside amidst a profusion of tall, lush

garden plants and wild vegetation in an area once

famed for its colony of artists. The mill we viewed

was originally one of two and this was the upper

mill. It is owned by a lady whose family worked it

for 500 years and she still lives in the Mill House

although we were a little disappointed to find the

mill locked and not opened to view as we had

expected, but we made do with peering in its window

and wandering down to the turbine housed in the

Lower Mill and powered by the tail water from the

Grade 2 listed flour mill above.

|

|

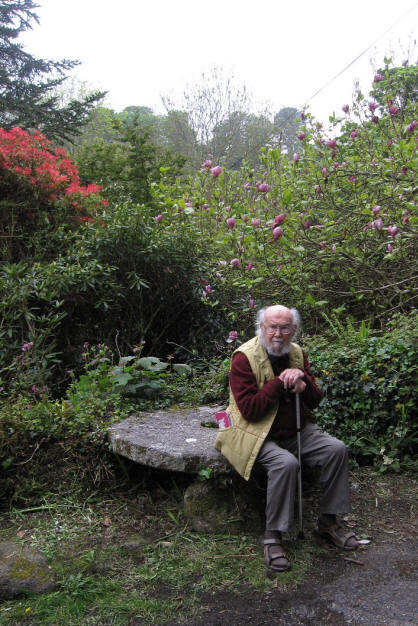

Tony Yoward was grateful for

the millstone left as a seat beside the Upper Mill

where he had a good view of the overshot waterwheel,

the shrouds of which were cast by Isaac Willie of

Helston in 1907. The wheel’s wooden buckets had

long since disintegrated. |

|

Historic England’s list entry tells us that this

particular building was probably erected in the 18th

century and comprises “Granite moorstone rubble

walls with some dressed moorstone. Grouted scantle

slate roof at rear, replaced with corrugated

asbestos at the front. Wheel has cast-iron hub and

segments, oak spokes. The machinery has been taken

out.” West Country mill historian, Martin Bodman,

states that Upper Mill has also been known as

Bossava Mill.

This visit to the beautiful and restful valley in

Lamorna gave a calming end to a day crammed with new

experiences and learning. This article concludes

the first of two – the second one, spilling the

beans on where we went next, will appear in the

Winter Newsletter.

A

record of the mines and other industries is

excellently presented in Industrial Archaeology of

Cornwall by A C Todd and Peter Laws, published by

David & Charles in 1972. It carries a dedication to

Rex Wailes for inspiring so many in the field of

industrial archaeology. |

|

|