|

|

|

Page 2 |

Newsletter 115, Winter 2016 © Hampshire Mills

Group |

HMG Autumn Meeting 9 September 2016

AGM, General Meeting and talk by Stephen Gadd

Alison Stott

|

|

On the evening of Friday 9 September

HMG members gathered at Warnford Village Hall for

our Annual General Meeting. Our chairman, Andy

Fish, welcomed everyone and also welcomed Stephen

Gadd. The meeting commenced with Stephen’s talk and

was followed by the AGM and brief general meeting.

|

|

Navigating the Avon from Salisbury to

Christchurch

in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods

Stephen Gadd’s talk as reported by

Alison Stott

Images from Stephen Gadd

|

|

Stephen Gadd started

his talk by showing us a picture of a ballad,

written in 1665, all about linking Salisbury to the

sea. In the 1660s considerable efforts had been

made to improve the navigation, despite the problem

of Christchurch harbour being so shallow. However

for some reason – possibly the closure of the priory

in Christchurch or the war with France in the 1690s

– these efforts were not successful, and trade began

to decline.

Four hundred years

earlier, in the 12th century,

Christchurch had both a priory and a castle and at

this time the process of engineering the river

began, with mill construction and deepening of the

river which enabled larger craft to use it, stone

from Purbeck being brought for the construction of

both priory and castle. Vessels could go upstream

all the way to New Sarum, bringing the material used

for building the new cathedral. |

Mills on the River Avon

|

|

Fordingbridge today |

There had been a

bridge, or ford, at Fordingbridge since 1086 and by

1240 the river had four bridges along its length.

Stephen showed pictures of the strip maps published

in 1675 and used by travellers to find their way

from place to place – clearly showing the crossings

at Downton, Fordingbridge, and Ringwood. |

|

There is indirect evidence that the

river was navigable in the 14th century. In 1372

the government commissioned military barges. One of

these was built in Sarum, despite its not being a

port, the cost being borne by the townspeople; all

over England the same thing was happening. The

French attacked in 1377 and more and bigger barges

were ordered – these could obviously reach the sea

and Stephen thought that only about 6 inches of

water would have been needed for the unladen barges

to make the journey downstream.

In the 14th and 15th

centuries the presence of mills and fisheries

impeded passage, and caused a conflict of interest

with the river’s use as a navigation. Climate

change in the late 13th century from wet

to dry led to a famine in Northern Europe in the

early 14th century, but was also blamed

on the shortage of mills to process the grain; on

the other hand there were complaints of ‘certain

impediments which are called locks’! These

‘impediments’ could be destroyed by law as the river

was, and still is, the King’s (or Queen’s) highway.

For example the Priory Mill was destroyed in 1535 in

order to allow navigation.

Stephen illustrated

flash locks on the River Thames, and suggested that

the rush of water these caused helped to keep the

river running faster and deeper.

In 1660 twelve mills

are recorded on the Avon; however there was a

further problem with navigation as the narrow

entrance to Christchurch harbour was silting up.

|

|

|

|

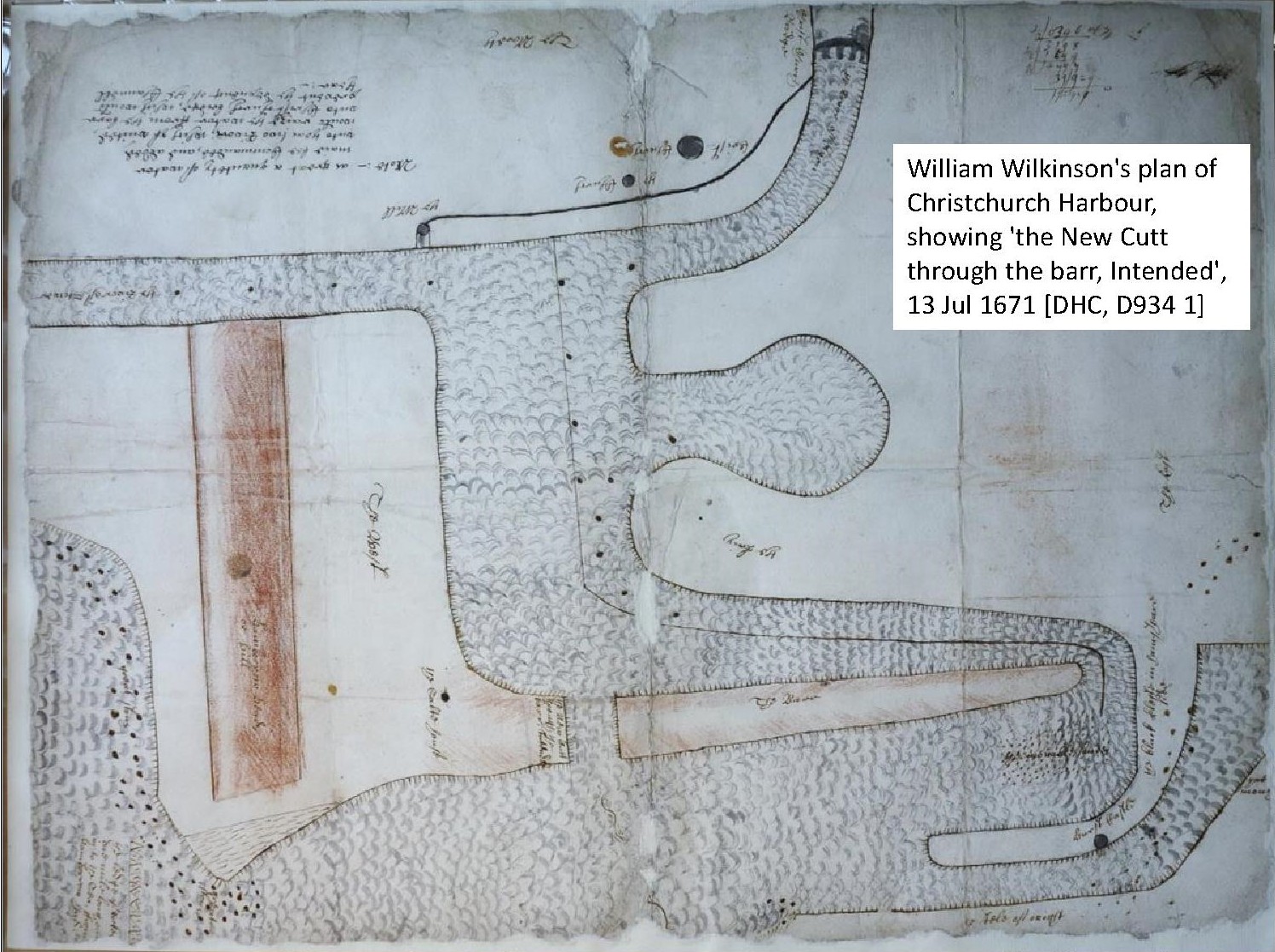

A cut that was proposed in 1670 was

begun in 1686; Mudeford Quay was built and

ironstone was used to make training piers. The new

cut made some difference as twenty six tons of coal

were recorded being shipped all the way to

Salisbury.

By 1854 further ironstone was being

mined from around Hengistbury Head, but

unfortunately this removed the protecting bank and

increased the rate of silting in the river mouth.

All the time Southampton was

competing for trade and Stephen thought that perhaps

restrictive practices there and the problems with

the silting up of Christchurch harbour eventually

led to the decline of navigation up the River Avon.

|

|

|

|