|

It was my aim to not write up all of this report.

As you can see I partially succeeded. Lots of

thanks to Andy Fish who not only arranged the visits

and accommodation, but also did all of the driving.

As you will read, it was a very varied and

educational tour.

|

|

Eagle-eyed Eleanor spotted this

machine plate at Kidwelly, but it is a good place to start. It left

us in some doubt as to which country we were in. |

|

Newport Transporter Bridge

Our first lunch break was at Newport

Transporter Bridge, where

4 intrepid HMG members (including photographer Ashok

Vaidya) climbed to the top and then across to bring

you this image of the gondola taking cars across

(and the less energetic members of the group! –

Editor).

Right : Looking up to see where we were!

Spot the man crossing the walkway

|

|

|

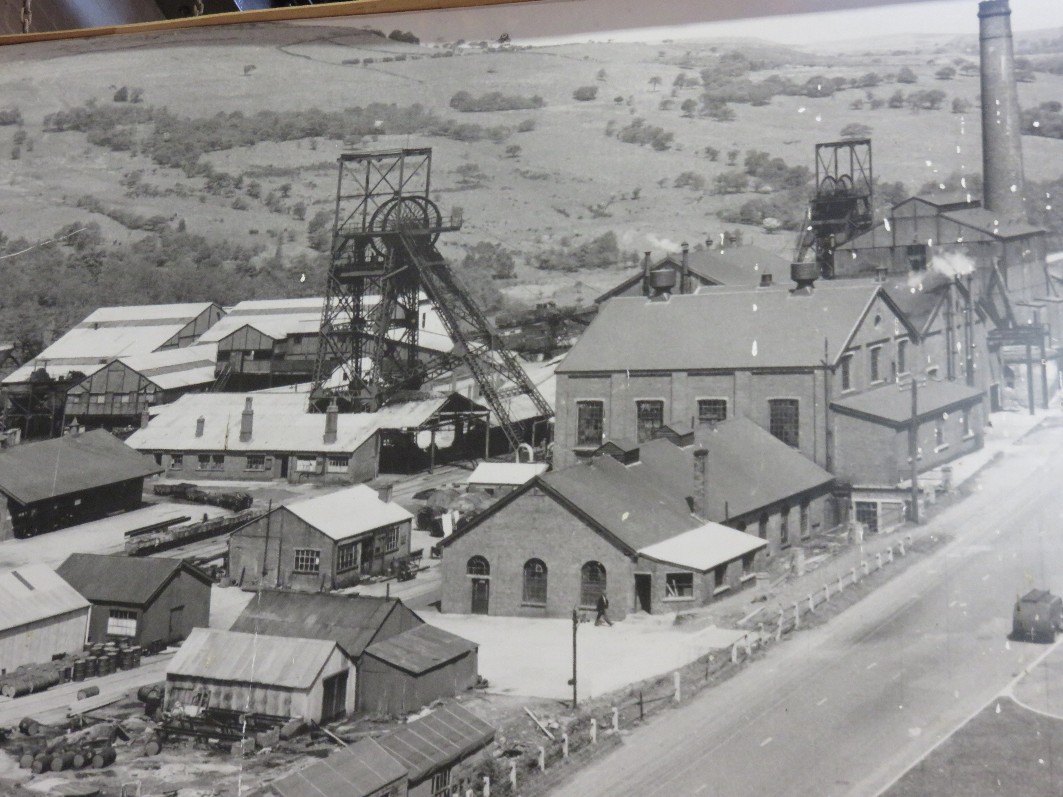

Cefn Coed Colliery Museum

Pictures by Mick Edgeworth and Ruth

Andrews

|

|

|

Mick Edgeworth says that in its day, this was the

deepest anthracite coal mine in Britain. They have

a unique surviving gas powered tram (without

machinery).

.  |

|

|

The mine’s headgear (as shown in the

historic photo on the left) now lies in 3 chunks at

ground level. This apparently makes it safer! but

definitely not photogenic.

We were conducted round the remains

of the site by 2 very knowledgeable former miners,

and even had a guided tour of the mock-up of a mine

interior, complete with a lesson on how to erect pit

props.

|

|

Kidwelly Tinplate Works

by Eleanor Yates

Pictures by Eleanor Yates and Ruth

Andrews

|

|

|

The Kidwelly

Industrial Museum Trust was set up in 1980 by a

small group of enthusiastic volunteers who wished to

preserve for future generations the history of the

hand mill method of making tinplate. The idea was

first put forward by William Hill Morris, the then

president of the Kidwelly Civic Society. Grants

were received from the Prince of Wales Trust, the

Science Museum, and the British Steel Corporation.

Llanelli Borough Council purchased the site and the

trust was granted a lease and applied for charitable

status.

Kidwelly, on the

Gwendraeth Fach river is the oldest surviving

tinplate works in Europe; it is mostly listed grade

2. It was obvious from the start of the visit that

water played a vital part in the tinplate works as

we were able to see the surviving brickwork and

sluices in the river and later the steam engines

which powered the works. Our guide, Malcolm

MacDonald, then took us into the first of 12

buildings (there are also exhibits outside) and

explained the very labour-intensive process of

turning iron or steel into sheets of metal ready for

tinning. This method includes rolling, hammering,

folding, and then bathing in hot sulphuric acid

followed by rinsing in water before the tinman could

put the sheets into the tinpot. Both men and women

were employed and the museum shows many photographs

of them, advertisements of their product and of tins

including those taken to Antarctica by Scott (see

below).

The museum includes

hot rollers, cold rollers, steam engines, shears,

gears, and a Lancashire boiler with a lovely demure

face (above right). Although it took several

hours to visit and would, if John Christmas had been

in charge, have taken a lot longer, we highly

recommend a visit to this museum.

For information look

at their

website and their

Youtube video

|

|

|

|

|

Carew Tidal Mill

by Ruth Andrews

|

|

|

By the time the group reached Carew

the minibus was running rather late, and the

prospect of a long leisurely lunch had completely

evaporated. Fortunately Alison’s son Angus came up

trumps by meeting us on the causeway with homemade

sandwiches which he had rapidly assembled following

an SOS from his mum.

Our visit to arguably the most

important site on the tour was therefore rather

rushed, and Andy didn’t get there at all as he had

to refuel the minibus.

The present mill, built around 1810,

was abandoned in 1937 but restored in 1972 by the

Carew Estate, which includes Carew Castle. It is

now again looking a little sorrowful (but very

clean). This is the mill which got me interested in

milling and I was shocked to find that my memory of

it was completely inaccurate. Anyway, here are a

few photos to give the general idea.

|

|

|

It has two 16ft undershot waterwheels with wooden

paddles, which have clearly suffered from being

flooded twice a day. I believe that by 1998 the

machinery and south waterwheel were operational, but

I doubt if they are now.

|

|

|

|

|

Tregwynt Woollen Mill

by Ruth Andrews

This compact and picturesque weaving

mill was once water-powered and houses an iron

overshot waterwheel, although it now turns only for

decoration. The fairly modern looms in a 20th

century lean-to machine shed at the rear of the

building are driven by electricity. 30 plus

employees make blankets, throws, cushions, and so

on, as seen right in the mill shop. The site’s most

popular feature is an excellent café. |

|

|

|

|

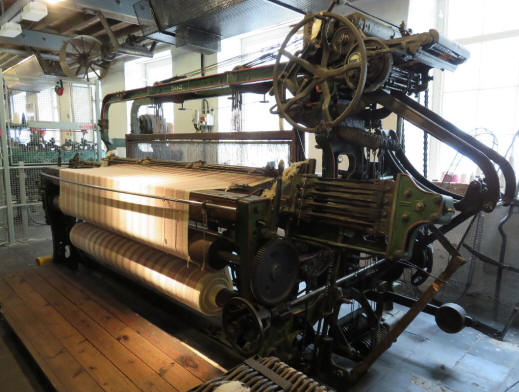

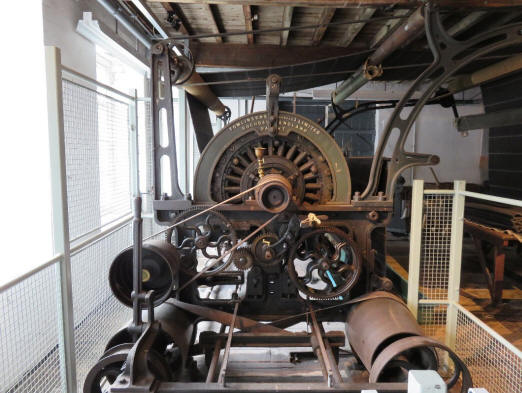

National Woollen Museum, Dreifach

Felindre

by Ruth Andrews

I asked the group participants to

each choose a site and no-one signed up for this

one. This is not surprising as it was a perfect

example of how to turn a very interesting museum

into something quite depressing. I don’t know what

these students from the Netherlands made of it,

jammed in this narrow aisle with us as well.

|

|

|

Inevitably the bale breakers, carding

machines, spinning mule, Dobcross looms, and so on

were all behind bars, and there was a sanitised room

full of glass cases with captive examples of woollen

garments and the ‘National Flat Textile Collection’.

Both the mill and the village of

Drefach Felindre are a national heritage site and

the museum re-opened in 2004 following a two year £2

million refit, partly funded by the Heritage Lottery

Fund.

|

|

|

|

Y Felin (The Mill), St Dogmaels

by Sheila Viner

Pictures by Sheila Viner and Ruth

Andrews

I fell in love with Y Felin. Who

wouldn’t on a balmy warm and sunny day?

The mill pond full of assorted ducks and geese

parading and quacking about; the relaxed old sofa

in the summerhouse doorway overlooking the pond;

and the mill built of stone set lower down fitting

snuggly into the incline leading to the Abbey ruins.

A second-hand bookshop is in the left-hand doorway

of the mill and then, through the right hand doorway

into the mill itself, there is a table covered with

hen, duck, and goose eggs, recipe and mill history

booklets. A high wall of shelves is stacked with a

surprisingly wide variety of flour types milled by

the owners, Michael and Jane Hall, smartly packaged

and beckoning buyers. The whole scene appeared

enchanting on this lazy afternoon. |

|

|

The Halls bought the small corn mill,

house, and mill pond in 1977 when the buildings were

in a dilapidated state and the pond filled with

rubbish. In 1941 the mill had been briefly used,

but otherwise it had been retired since 1926 after a

well-chronicled life spanning eight centuries dating

back to ownership by St Dogmaels Abbey, when it is

thought to have functioned mainly as a fulling mill

(1291).

They set about restoring it to

working order in 1980 and, a year later, reflooded

the millpond. Mr & Mrs Halls’ diligence paid off

and the mill gained Grade 2* listing in 1993 from

CADW. Royalty descended in 2003 to the village of

St Dogmaels on the Cardigan Bay estuary, and HRH

Prince Charles and his wife, Camilla, called in to

see this little three-storeyed mill at work. |

|

|

|

Cwmdegwel, a tributary which feeds

into the River Teifi, powers the overshot 16ft metal

wheel. When we visited, the wheel’s buckets were

alarmingly leaky, the water gushing at great speed

in all directions where the buckets weren’t whole

(some of them wholly full of holes) but at the same

time the wheel’s activities loaned a homely

quirkiness to the atmosphere of the place. I do

hope those wheel buckets are repaired sometime soon

as a lot of energy is lost with each turn of the

wheel.

I later learned that the iron wheel

shrouds came from Grade 2 Listed Felin Asaf (Dewiston

Mill) at St Davids which otherwise still has all its

machinery in situ and is now part of a holiday home.

Three pairs of stones plus dressing

and sifting apparatus are on the first floor and the

meal chutes deposit the flour to the weighing and

bagging area behind the shop.

|

|

From his three sets of stones,

Michael produces unbleached white, garlic and chive,

seed and herb, malthouse, self-raising, 100% rye,

rolled oats, and bran as well as the ever popular

100% wholemeal flour – a staggering menu of flour

types which must keep him and Jane very busy – and

they retired for a quiet life! |

|

|

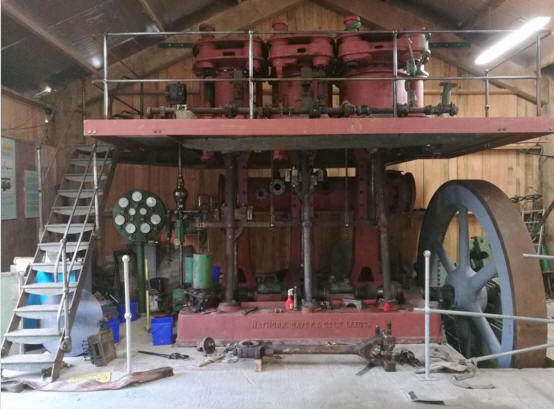

Internal Fire Museum of Power

by Andy Fish

Pictures by Andy Fish and Ruth

Andrews

On the Saturday of our trip to Wales we visited the

Internal Fire museum at Tanygroes, Ceredigion. The

museum was founded in 2003 and was set up to cover

the history and use of large engines in the 20th

century. It houses a wide range of working exhibits

with engines running daily. A selection of smaller

engines runs all day

from 10:30 until 5:00, larger engines are

started as people come and go. Recently it has been

decided to construct a Steam Hall to save and

restore stationary and marine steam engines to

working order. This includes the Hathorn-Davy

triple expansion steam engine from Wessex Water’s

pumping station at Sutton Poyntz near Weymouth in

Dorset; the engine arrived at the end of January.

These photos show the progress by the time of our

visit in mid-May.

The members who came on our study

trip to Dorset organized by John Silman and Tony

Yoward around eight years ago will remember our

visit to Sutton Poyntz where this engine was stored

outside under tarpaulins awaiting its fate.

For more information go to

www.internalfire.com.

|

|

|

|

Hetty Winding Engine

by Ivor New

Pictures by Ivor New and Ruth Andrews

The

shaft that was later to be called Hetty was sunk in

1851 to locate and extract anthracite, the then

favoured locomotive fuel. Great Western Railway

interests obtained control of the pit and together

with five additional pits became known as the Great

Western Collieries.

The shaft was named Hetty in 1875

when it was deepened and had its Barker and Cope

steam winding engine installed. Hetty was the

owner’s niece who performed the opening ceremony by

breaking a bottle of wine on the winding drum.

|

|

|

|

The engine was later rebuilt by

Worsley Menses who added piston expansion valves.

Later still limiter equipment was added

(illustrated), as a safety measure, to stop over

winding.

Hetty

is like a venerable old lady who when younger was

present at all the major events of the day and

hasmanaged to survive, mainly due to her current

comparative insignificance. Relatively early in her

life the shaft shifted out of alignment during a

landslip. Hetty was then removed from production

work and used as a ventilation and maintenance shaft

until the Great Western colliery ceased working.

She was then utilised by an adjoining colliery as a

personnel lift. When, in turn, that colliery shut

in 1983 the significance her industrial heritage was

realised and she received a Grade 1 listing.

|

|

On 1 March this year The Great

Western Colliery Preservation Trust signed a 30-year

lease to enable it to look after this important

site. To celebrate the event the engine was

operated using compressed air. It is hoped this

will become an annual event taking place late each

September. |

Operator's Station

|

Winding

Drum |

|

Blaenavon Iron Works

Our final visit of the tour was to

Blaenavon Iron Works, principally for a lunch stop,

which turned out to be sandwiches from the Co-op.

The site has extensive remains of several blast

furnaces and casting houses (left), and a prominent

water balance lift (right).

Thanks to everyone for a stimulating

and enjoyable tour, even if it wasn’t all mills.

Andy is already considering next year – maybe North

Wales. |

|

|