|

Mills in the Monts du Forez

Ruth Andrews

Photos by Keith and Ruth Andrews

|

|

We have just returned

from 2˝ weeks in the south of France. Our first gîte

was in the little known district of Forez, with a

wonderful panoramic view across the upper Loire

valley: “on a clear day you can see Mont Blanc”,

although we never did due to the heat haze.

|

|

|

|

In the village of Sauvain, a few miles from the gîte,

we were interested to see this

Fontaine des 5 Meules.

It is madeup of 5 large millstones, 2 for milling,

and 3 for crushing, which was built by the villagers

in 1968. The meules (millstones) came from abandoned

former mills in the locality. The same village also

had an unusual iron waterwheel on display outside

the museum (closed even though it was Sunday!). Just

outside the village was this cross mounted on 2

millstones. |

|

|

|

Moulin des Massons

is very heavily advertised locally so we went there

expecting something that was very commercialised.

We dutifully joined a conducted tour – in French, of

course: overlong at 2 hours as is the French way,

but thankfully there was an leaflet in English as

well. Anyway, we were rewarded with a really

interesting visit.

|

|

This mill is the last of almost 70 that were on the

Vizezy river, and the site dates from about the 12th

century, although the present mill building has been

rebuilt several times due to flood damage. It has

been used for flour milling, clover crushing, hemp

processing, generating electricity, and as a

sawmill, but now it demonstrates oil production.

We were

treated to a demonstration of its production, which

was unfortunately not a slick performance.

|

The mill itself is one of a cluster of buildings

which also include a farmhouse and sawmill. Various

objects scattered about the grass outside included a

clover mill, several disassembled turbines, and a

Pelton wheel.

|

|

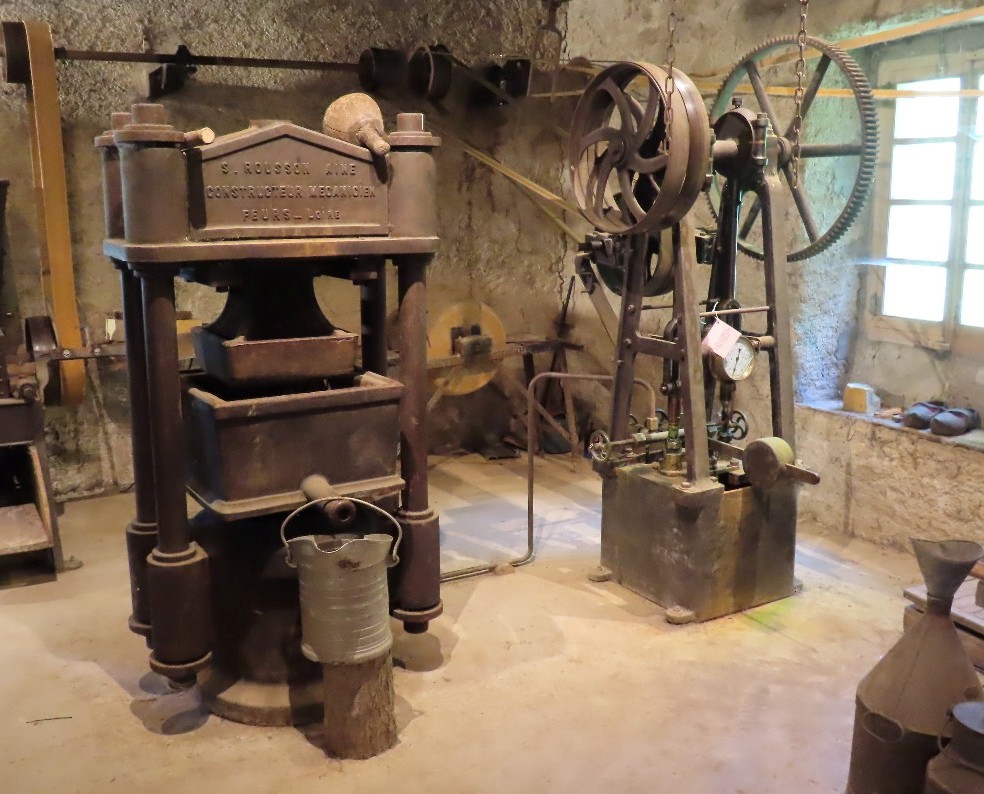

First the seeds are crushed between a small pair of

metal rollers, which jammed at first because the

‘miller’ put too much in. Then they are transferred

to a large stone crushing mill with sweeps (above

right).

When ready, they are carried across to a large

frying pan over a pinewood fire (left).

The crushed seeds have to be continually stirred by

hand and by sweeps to prevent them burning.

Once judged

to be cooked they are scooped out into a cloth-lined

oil press packed tightly and squeezed to release the

oil into a bucket. (At first, the miller put the

cloth lining in wrongly.) Power for the oil press

came from a hydraulic piston some way away behind

the viewing gallery where it sprayed lubricant onto

the spectators. The rest of the processes were

belt-driven from a horizontal wheel (a turbine?)

below floor level, viewable in a mirror.

|

|

|

|

The oil is

purified (elutriated: look it up!) before bottling.

Keith staged a tactical retreat at this point but I

dutifully sampled teaspoonfuls of noix (walnut),

noisette (hazelnut), and colza (canola) oil, all of

which are made on site. I then left rapidly to gulp

tap water and suck a Werthers to get rid of the

taste! Needless to say, we didn’t buy any. |

The same

‘miller’ also gave us a demonstration of the sawmill

which operates alongside the oil mill. The band saw

in use was completely unguarded and sprayed sawdust

over the audience, while the miller didn’t use

goggles, or gloves, or any other protection. |

|

|

The oil is

purified (elutriated: look it up!) before bottling.

Keith staged a tactical retreat at this point but I

dutifully sampled teaspoonfuls of noix (walnut),

noisette (hazelnut), and colza (canola) oil, all of

which are made on site. I then left rapidly to gulp

tap water and suck a Werthers to get rid of the

taste! Needless to say, we didn’t buy any.

We visited

Le Moulin de Vignal

at Apinac

several days later. We knew it was not a day when it

was open, but we struck lucky because a large party

of primary school children were lining up to go

inside. A second set were picnicking in the grounds

and I think a third set were expected later. The

second set had made their own bread hedgehogs and

were all very enthusiastic. The other set were

sitting attentively through a long explanation of

the mill’s workings and products: flour until 1940,

canola until 1960, and then animal feed and clover

seed. We were given a guide sheet in English and

invited to look around on our own.

The mill was named after the family who have lived

in the area since 1650. The main buildings were

constructed in 1773 and 1860. When the last miller

died in 1991 a group of villagers decided to rent

the mill from the family in order to repair the

buildings and mechanism, and then open it to

visitors.

|

|

|

The mill has always relied on water power, with two

working horizontal wheels inside (one wood, one

metal) and a vertical overshot wheel on an outside

wall. There are 4 sluice gates in the mill head

which control the water supply from a dam some way

upstream.

The overshot

vertical wheel drives a pair of stones used for

milling flour. The metal horizontal wheel (below

left) powers the meal mill for animal feed, while

the oil mill uses belts and pulleys to connect it to

the wooden horizontal wheel (below right).

|

|

|

|

|

A separate open-fronted stone building further down

the slope contains a circular trough and crushing

stone for breaking clover pods. The seeds are used

as animal feed but also planted: clover is a legume

which has root nodules containing nitrogen-fixing

bacteria, which add nitrates to the soil and are

therefore natural fertilisers. The crushing process

generates a lot of dust which is why the mill is

situated in an open building.

See also

https://moulindesmassons.com/

and https://www.moulindevignal.fr/

|

| |