|

|

|

Page 4 |

Newsletter 137 Summer 2022 © Hampshire Mills Group |

|

The Miller, the Maltster, and the Merchant

Robin Appel

|

We write a lot about mills, but rather less about

the millers who operated them. The likes of Joseph

Rank and Joel Spiller became household names, but

for most of the rest, the vital role they played in

the community in their day has long been disregarded

along with too many of their former premises. Yet

they were such an important part of our history, not

only providing one of the vital staples of life, but

also a range of job opportunities, often across a

wider spectrum of rural industry, and occasionally

delivering acts of philanthropy that benefited

everyone.

The thread of this story is that it was not unusual

for the miller to also combine the activity of

maltster, provider of another of life’s staples,

and, sometimes, the activities of both corn and coal

merchant.

Miller/Maltster

Perhaps the most compelling and surviving example of

a miller/maltster (as I revealed 4 years ago in

newsletter 123, Winter 2018) is the one right under

our very noses in Hampshire, sat astride the Eling

Causeway. Here, the mill is described as having two

Poncelet water wheels, each driving a pair of

stones, one pair for grinding wheat into flour, the

other pair, according to the official guide (Eling

Tide Mill, the history of a working mill, Diana

Smith), for crushing ‘barley for malt making’, but,

let us get it the right way round, actually for

crushing malt ready for brewing. The malt came from

what now transpires to be the adjoining malthouse

(previously described as an adjoining grain store)

which now houses the sailing club. The buildings

are described in 1933 as ‘communicating’, so it

would be difficult to believe the two activities of

milling and malting were ever separate businesses.

|

|

The Mill at Burnham Overy, Norfolk,

behind which sits the Malthouse

|

In the centre of Lyme Regis, in Dorset, the Town

Mill sits right next to the maltings, and at Burnham

Overy in Norfolk, the mill sits astride the River

Burn, while the maltings is immediately adjacent on

the eastern bank of the mill race. These two

examples could have each involved a separate

proprietor, but both milling and malting were

prosperous ‘first process’ activities derived

directly from the annual corn harvest. |

|

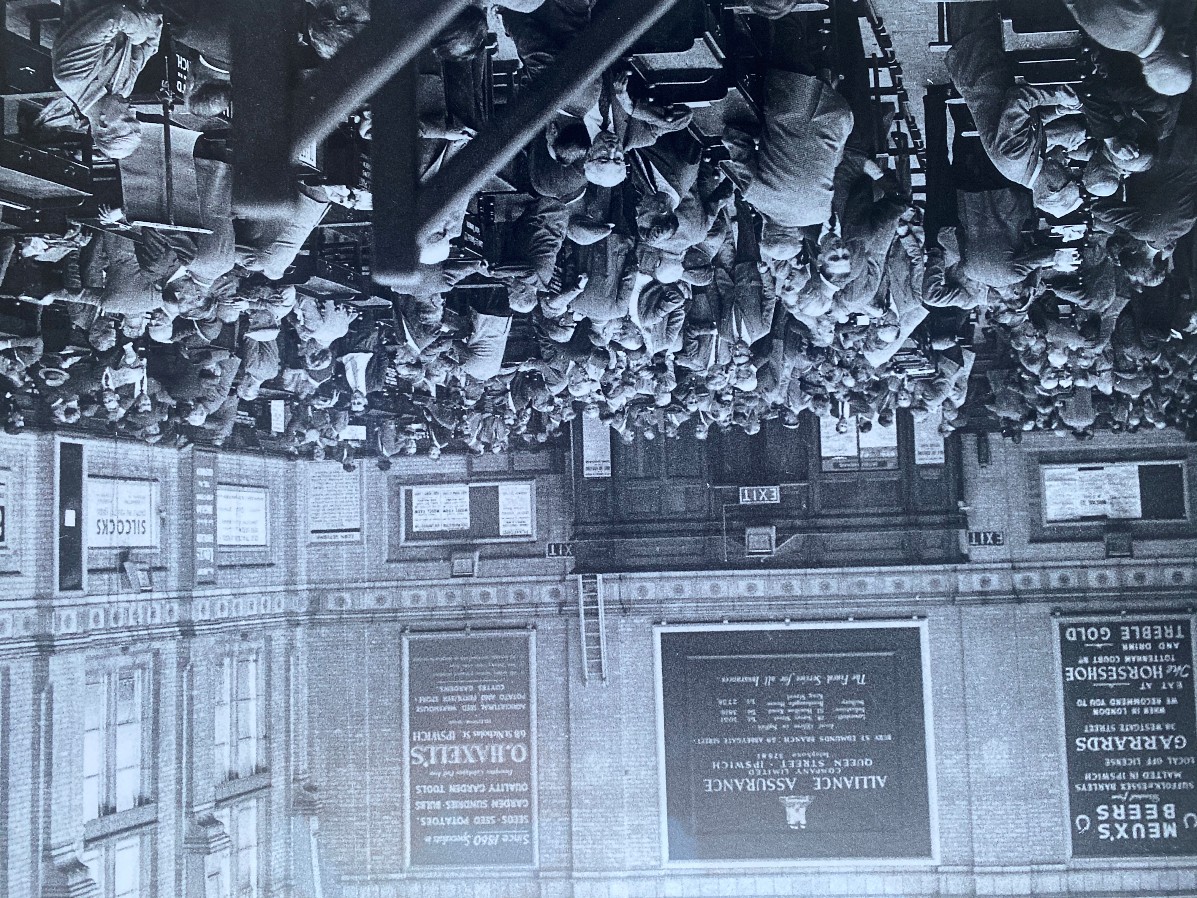

The combined trades should not surprise us, as when

attending the local corn markets to review the

harvest, as Newson Garrett (1812-1893) of Snape

Maltings, in Suffolk, made a point of doing (Port on

the Alde, Julia Philips), it would be difficult not

to talk to farmers about the yield and quality of

their wheat crop at the same time as inspecting

their barley. Besides, in those days, farmers were

particularly loyal to the miller, maltster, or

merchant they preferred to sell their corn to. It

was certainly not acceptable practice to hawk your

grain samples around different buyers. In fact,

quite the opposite, if you had no buyer lined up,

you presented your grain at the local Corn Exchange,

and had to wait for a buyer to find you! So it was

particularly convenient for farmers if a single

customer for their corn performed a range of

activities which secured them a market for all the

corn they had to sell.

More than Milling and Malting

But that range of activities very easily stretched

beyond just milling and malting. It sometimes

included the role of corn merchant. Back to Eling

Tide Mill, in 1785, the then proprietor, John

Chandler, was described as ‘a prosperous and

enterprising corn merchant’!

If farmers were to continue growing the preferred

varieties of wheat and barley their customers

requested, every so often they needed to purchase

‘new’ seed corn. Back along, this would be derived

from the ‘finest quality’ grain, originally

purchased for processing into flour or malt, but

then put to one side, re-cleaned over a dresser, and

delivered back out to farms for sowing. As recently

as the 1960s this was still a substantial source of

seed sold to farmers under two fanciful headings

‘Field Inspected’ and ‘Field Approved’. From my own

experience ‘Field Inspected’ involved very few steps

beyond the field gate prior to harvest, although

‘Field Approved’ was a bit more thorough, both in

the field and in the seed store.

But selling seeds to farmers was probably not as

profitable as milling or malting. Back in the 19th

century, Edwin Tucker, a farmer in Devon, set

himself up as a seed merchant, but then chose to

expand into malting, eventually operating up to 5

different malthouses. His son, Parnell Tucker, went

on to build one magnificent new maltings, in 1900,

alongside the railway track in Newton Abbott.

(Parnell didn’t stop there: he eventually

graduated to an even more lucrative occupation, as a

brewer, in Exeter.)

|

|

But for millers and maltsters, if trading as a

merchant (of seed corn) was perhaps a means to an

end, it sometimes went even further still. When I

was a boy, brightly liveried lorries plying their

way along the country roads of East Anglia regularly

carried the description ‘Corn, Seed & Coal

Merchant’. There was a historical reason for the

inclusion of coal.

|

Ipswich Corn Exchange crowded with Corn Merchants,

Tuesday, September 3rd, 1963. (Photo purchased from

East Anglian Daily Times)

|

|

We are talking about the days of on-farm rick yards

when the harvest was bundled into sheaves,

originally by hand, then courtesy of the binder.

Come the winter, the stacks of barley and wheat had

to be threshed, normally by a visiting contractor

whose main source of power was a steam powered

traction engine. This operation could stretch over

a week or more and required a lot of coal. The

merchant would traditionally supply the empty sacks

for the grain, and the coal for the steam engine,

all of which was probably deducted from the

remittance for the corn. But, of course, as coal

merchant to the farmers, it was very difficult not

to be coal merchant to the remainder of the local

community. My grandfather’s substantial barley

merchant’s business ended up with 6 full time

employees performing the role of coal merchant,

including 3 delivery drivers with regular rounds

across half a dozen parishes or more.

River or Railway

Where possible, many mills were constructed

straddling a reliable water course, but with the

coming of the railways, maltsters and merchants were

better situated alongside the tracks. Quite apart

from the easier access to coal supplies (maltsters

for their kilns, merchants for the traction

engines), the barley trade itself very quickly

centred around the rail network. By the beginning

of the 20th century, and long before dual

carriageways, the need to deliver vast quantities of

malting barley from East Anglian and Wessex farms to

the huge malthouses of the national brewers in

London, the West Midlands, and the north of England,

struggled with the horse and cart, the canal barge

,or the early motor lorry. . |

|

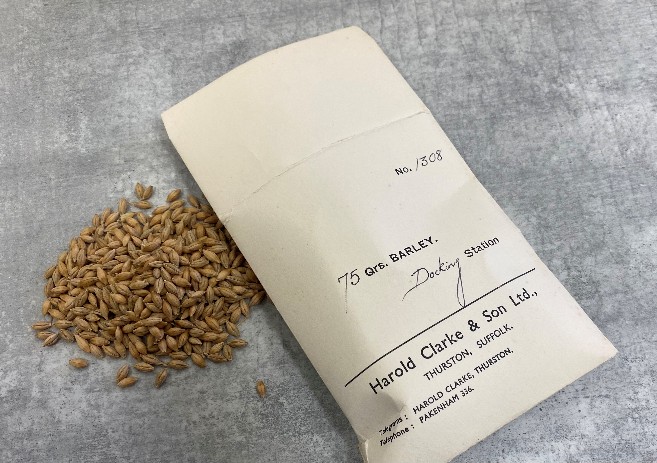

So farmers needed to deliver their barley to the

nearest railway station for forwarding, either to

their immediate customer, or to the next or final

customer for their grain. As a result, Merchants

sample bags (right) representing individual parcels

of malting barley were printed accordingly, naming

the ‘Station’, that is, the railway station, closest

to the farm where the barley was grown. |

|

|

The village of Docking in Norfolk had a railway

station, which became a favourite source of malting

barley in ‘The Brewing Capital of the World’,

Burton-on-Trent. As soon as this became wider

knowledge, merchants took advantage. If a

particular sample of malting barley failed to find

favour on Bury St Edmunds’ Corn Exchange on a

Wednesday afternoon, the merchant would take it

home, re-package it in a sample bag naming Docking

as the station, and the parcel would readily sell on

Norwich Corn Exchange the following Saturday

morning! As a result, Docking railway station

became massively oversubscribed with consignments of

malting barley, some finding their way there from as

far afield as the wrong side of the Suffolk border!

A Legacy Worth Protecting

Alas, today there is only a limited trace of our

former malthouses, more often than not just a street

name like Malt Lane, Bishops Waltham. In Dereham,

Norfolk, and Ipswich, Suffolk, two spectacular

blocks of flats are forever former Malthouses,

thanks to the signature architecture of the ‘pyramid

style’ kiln roofs that the developers either chose,

or were compelled, to retain. But there are few

similar examples. Merchants’ former granaries have

long since been swept away.

In glorious contrast, our water mills, sometimes

with adjoining Georgian-fronted houses, punctuating

our smaller rivers, have not only survived in large

numbers, but have evolved into the ‘chocolate box’

image of the perfect pastoral setting. That so many

of them also retain parts, if not all, of their

original infrastructure, is truly remarkable.

Not only that, we have the legacy of John Constable

who chose to illustrate them (Flatford and Parnham

Mills), George Eliot who chose to write a classic

novel around The Mill on the Floss, and

Ronald Binge’s musical composition The Water Mill

which only serves to immortalise the romantic

image of ‘dusty miller’!

Why! oh why! I continually ask myself, was the

maltster, that key provider of the other staple, so

overlooked? Any advance on Warren’s Malthouse in

Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd? |

|

Benjamin Britten chose Snape Maltings because, when

four of its former kilns were gutted, it was

uniquely big enough to convert to a concert hall,

and it was close to Aldeburgh, his home. I do not

believe he had any particular interest in preserving

the image of malting.

As for the merchants, they have almost sunk without

trace beyond - Thomas Hardy again – The Mayor of

Casterbridge whose trading folly has been

re-enacted over and over throughout the last 50

years. No lasting legacy there, only ignominy!

So, I suggest, it is vitally important we retain a

watching brief over our mills, in order to protect

them. We do so need formalised groups who can speak

up for them, and support them. As Clive Aslet wrote

recently in Country Life, of old houses, so too our

mills: “they are a record of our past”! And we

should not rule out that one day, the same concept

could even be re-invented.

|

Musical Malt Kilns |

|

|

|

|